Amazon greenlights television series inspired by Mafia Princess by Marisa Merico

16/05/2019

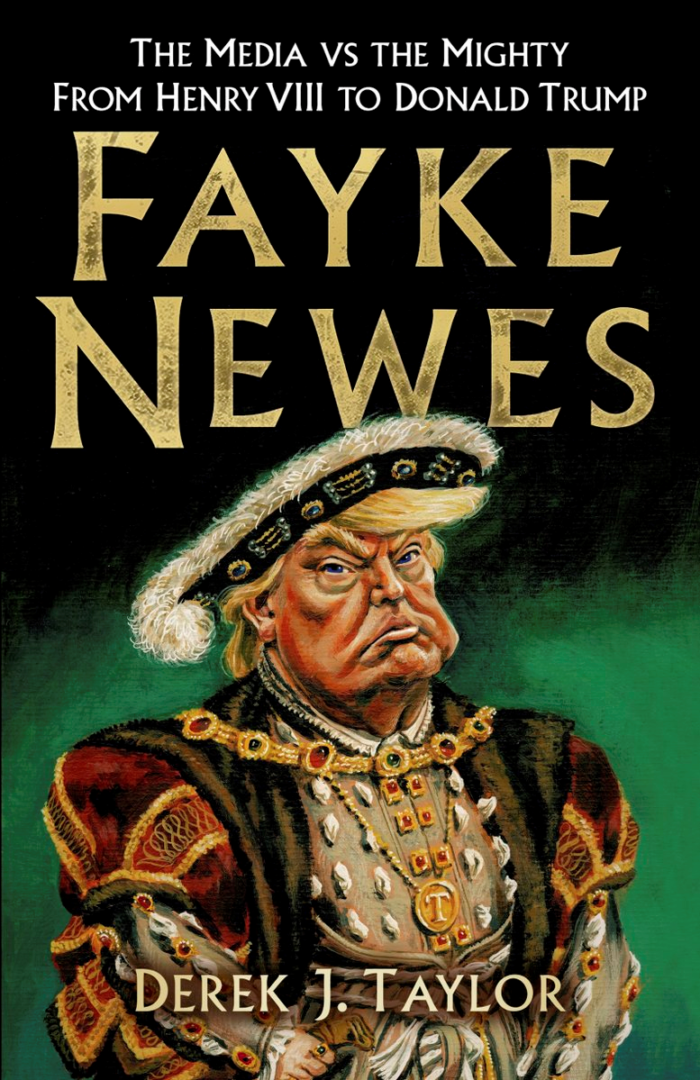

Before he was a writer and historian, Derek Taylor reported from some of the world’s most dangerous war zones. He was ITN’s first Middle East correspondent and spent seven months in Iran during the Islamic Revolution. Derek tells us how his experience as a journalist helped shape his new book, Fayke Newes: the media vs the mighty from Henry VIII to Donald Trump, published on 2 July by The History Press.

At five o’clock on the morning of 13th March 1978, with next to no sleep, my ITN film crew and I crossed the border north into Lebanon in the tracks of the invading Israeli army. It was to be my first taste of war-reporting. Actually, that first day, it was a bit of a disappointment. All we saw were columns of tanks throwing up dust as they pressed on into the Lebanese mountains. But it would have to do.

Back in Israel by mid-afternoon. I was preparing my film report. By 7 p.m., as I lit my 50th cigarette of the day, I was ready to add a commentary to the finished edit.

At that moment, the door opened and in walked an unsmiling young woman in civilian shirt and slacks. She introduced herself as the military censor, and explained she had to make sure I wasn’t giving away any secrets to Israel’s enemies. She listened while I did a practice run-through, talking over the couple-of-minutes-long report.

‘Right,’ she said, ‘You need to cut out the words “The Israeli bombardment of these villages is a punitive retaliation.” That’s wrong. This is a surgical operation to remove the terrorists’ base.’

‘But that’s got nothing to do with security,’ I complained.

‘You know,’ said the censor, ‘I’m thinking there’re a lot of your pictures which might show identifiable, security-risk locations. I’ll have to consult my boss. It could take a few hours.’

‘A few hours!’ I exclaimed. ‘But I’ll miss tonight’s News at Ten.’ And then I got it. I couldn’t transmit my report to London without the censor’s permission. Cut these words, or lose the whole thing.‘OK, OK,’ I said. And the report went out to the censor’s – rather than my – satisfaction.

Four months later and 5,800 miles west of Israel, such was the life of a general reporter that I now found myself in Washington DC. I was sitting alongside a dozen other journalists at an off-the-record briefing on Capitol Hill with a US government bureaucrat telling us when and how we’d learn the results of the official enquiry into the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King. Dull detail, no story that day.

One of my fellow reporters asked why we hadn’t been permitted to film this afternoon’s briefing.

‘Well,’ replied the official, ‘this meeting isn’t what matters. We want you to report on the committee’s findings, not the process.’

The questioner jumped to his feet. ‘Don’t you tell us what we can or can’t report!’ he snapped, jabbing a finger towards the now flinching bureaucrat. ‘We know our job. You stick to yours. We’re not here to be jerked around by you or anybody else in government.’ Seemed a bit rude to me. But there was a smattering of applause around the room and enough ‘Yeahs’ to indicate he was speaking for the rest of the hard-nosed Washington press corps.

This was post-Watergate Washington. In 1974, the leader of the free world, President Richard M. Nixon had been forced to resign when two reporters from the Washington Post revealed his administration’s attempt to cover-up a break-in at the Democratic Party’s Watergate offices. As a result, journalists in late 1970s USA now had an aggressive sense of their mission.

The contrast between these two experiences has stayed with me. In Israel, the authorities had held the whip-hand. In Washington, it had been the reverse.

Governments and journalists have always been natural enemies. And that’s what I explore my latest book, Fayke Newes: the Media vs the Mighty from Henry VIII to Donald Trump. It’s been a long, messy, at times bloody battle. At stake, the truth – on which our very democracy depends.